I. the silence

Like many unplanned hiatuses, the silence from this newsletter has been caused by a type of mess. I tend to call it The Mess whenever I see it. And that’s not a judgement. It’s not preventable. And, if you have any doubt about what it refers to, it just hasn’t happened to you yet.

I. the balance

It’s not extraordinary, really, to experience it. When you try to make a life, balance it like blocks, and have them all fall. It’s not even abnormal for our childhoods to be shaped around the collapse of our parents’ lives, scattered either in post-divorce moving boxes or evident in the pocked old shelves, making clear for the first time what belonged to who all along. Or for those boxes, like our feet, to be finding purchase on unfamiliar floor tiles in a new house, emptier than you imagined a house could be.

That’s just the thing about it. Your parents probably didn’t get married thinking they’d get divorced, and neither did you. The mess comes for all of us, no matter how strictly we ordered our lives, or what philosophies of acceptance and adaptation we embodied. The meditation, the eating dis-orders, the dancefloor chaos, that ringing-of-the-ears and crick-of-the-neck headbanging pleasure aftermath. Or the serene pleasure of a coffee shop outing, the mild sting of the waitress misgendering you, the fact that you find yourself able to take it and still have a good day. None of it made any promise against entropy, but you let yourself believe it did. I’m only a little sorry to be predictable here and quote boygenius yet again, but they really cooked when they said “Oh, it hurts to hope for more / Oh, it hurts to hope the future will be better than before.”1

I watched a movie recently; The Boy and the Heron by director Hayao Miyazaki, and this is me writing about it.

II. writing about a movie

I watched The Boy and the Heron (2023) with four strangers at Cape Town’s iconic Labia Theatre. The five of us, brought together by a social group for nomads (and, I suppose, the socially displaced too) managed to speak for perhaps 10 awkward minutes before heading into the film, 10 minutes late, barely hearing each other over the din of a red carpet premier happening at the same time.2

The Boy and the Heron is only the second Miyazaki film I have ever watched in a theatre, the first being Spirited Away all the way back in 2001, when I was 7 years old. While Spirited Away came to me during my parents’ divorce, I came to The Boy and the Heron at the beginning of mine. It’s funny how life works. It’s funnier how it doesn’t. So both films happened to me during times of great personal upheaval. And because Spirited Away gave me a world of magic, wonder, and self-discovery to escape to, I found myself hoping that the newest synthesis of director Hayao Miyazaki and composer Joe Hisaishi would similarly comfort me now at the end of my 20s. After all, even in-between my parents’ divorce and mine I otherwise had a wonderful time (maliciously revisionist take), occasionally watching Miyazaki’s other films like Nausicaä of the Valley (1984), My Neighbour Totoro (1988), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), Ponyo (2008), etc.

Each of these earlier films, in their own way, advocated for a belief in the benevolence of magic and fate, and are narratives about certain kinds of triumph over loss. At 83 years of age, and 24 years into a century that he “wants nothing to do with,”3 Miyazaki has produced a film that is desperate, volatile, arduous, and precarious. Its moments of levity don’t quite land as humorous or relieving. The parakeets are a slapstick, technicolor regime of violence, consumption, and control. The titular heron, when he loses his powers, resorts to feeble flapping of his wings to get around, with a mosquito-like whine to emphasise his weak and ailing body.

II. being angry at a composer

Protagonist Mahito navigates the incessant pain and confusion of the changing worlds around him with singular focus: He will save his aunt from a fate that awaits her, and, if possible, save his mother from a fate that has already befallen her. As he is between childhood and adulthood, between home and away, between fates, and between worlds, Mahito heeds nothing but his own impulses, even when the same instinct guiding him to protect others leads him to self-harm.

Considering my own recently volatile circumstances and the inwardly-focused spirals, I went into Screen 4 at The Labia with my group of far-removeds, ready to feel elation and hope the way Spirited Away’s magic worked when I first watched it. I was ready, especially, to be carried through a new otherworldly journey by another of Joe Hisaishi’s immaculate and animistic scores. Except this time, Hisaishi and Miyazaki were clearly not intending to evoke anything like what I expected or wanted. Rude.

The Boy and the Heron is a peculiarly abstract and philosophical journey that doesn’t linger on any visual concept or musical idea. The effect it produced in me was a desperation to find something to cling on to through the film, something or someone that will be constant, who will be with us from the start of this journey until the end. But everything keeps changing. The ideas we keep forming to stay abreast of the story can’t keep up and crumble, unable to match pace with one existential epiphany after the next. It’s a mess of a movie. A good one. And it forces you to rely on patience to keep enduring through a narrative that has no predictable structure, no cathartic moments of Miyazaki skies or ma,4 until we find peace or don’t, until peace comes or doesn’t.

III. the hole in your chest

My problem may have been that while I watched Spirited Away with no emotional expectations, I went into The Boy and the Heron with vast emotional needs.

II. exquisite catastrophe

According to Shy Thompson, who reviewed Hisaishi’s The Boy and the Heron score for Pitchfork.com,5 Miyazaki and Hisaishi’s working relationship had changed for this film. Previously, they were deeply involved in each other’s creative processes. This time, however, Miyazaki showed Hisaishi a nearly-completed version of the film and left the rest in his hands. This level of trust shown to Hisaishi by Miyazaki reflects another of the story’s themes: relinquishing power and responsibility to another whose work will always, in essence, be unlike yours.

Mahito’s grand-uncle, a god-like figure living between worlds, has dedicated himself to the solitary task of keeping the entanglement of realities in harmony. His work as an animistic sorcerer who has sacrificed his own life to the care of all of reality, remains unexplained. Mahito travels through time, fights avian fascism, climbs a mountain of magical blocks to meet his deified grand-uncle… and then there’s just a meteor, too, on top of every other damn thing. Hovering just above them and emanating strange powers of balance and control and utopia. Moments later, The King destroys it. A disaster.

Inscrutable. Exquisite.

I. do you find yourself wandering?

One thing about a mess is that there is no truth to it. Just a hundred angles on a catastrophe.

III. i do

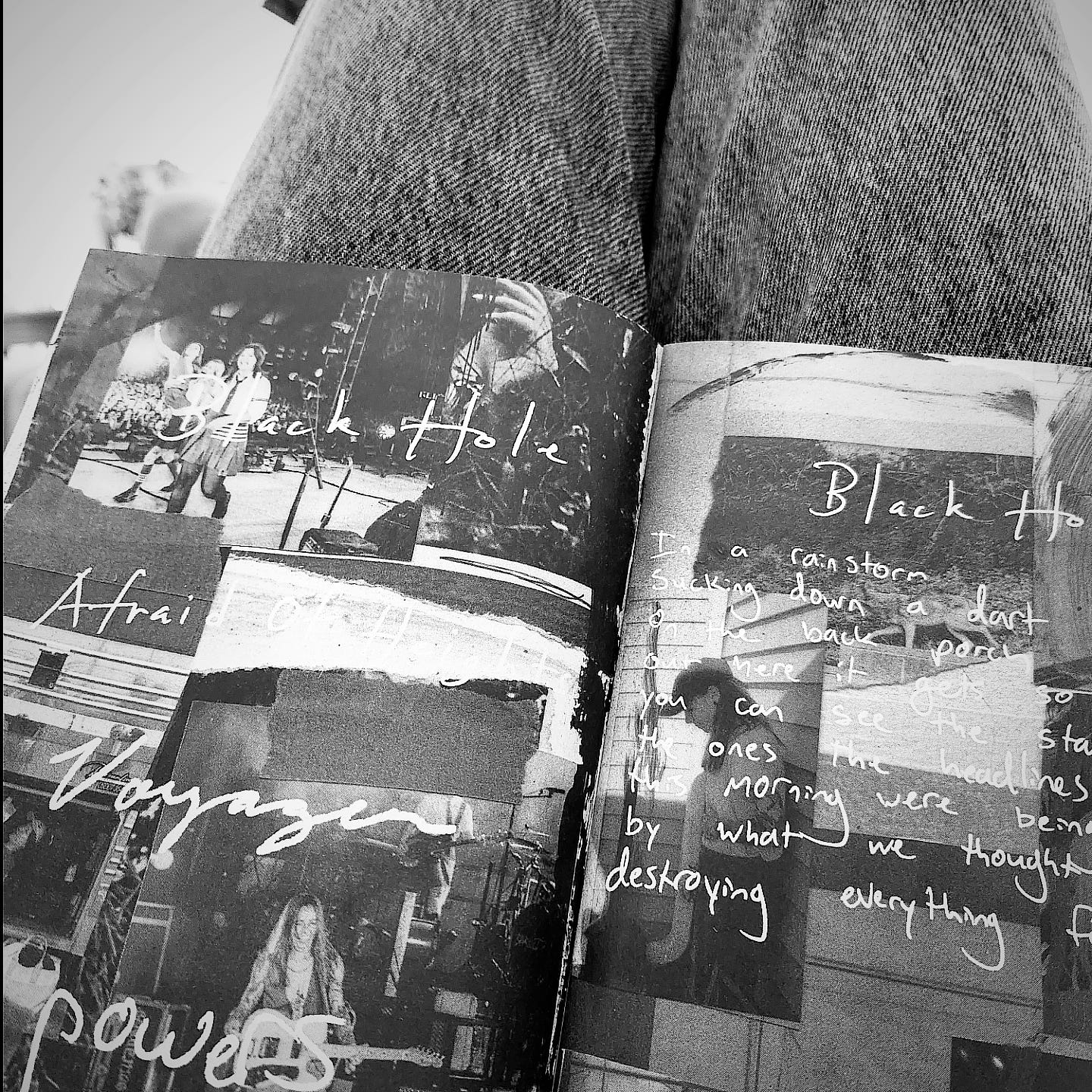

I was writing midnight poetry when I realised that Taylor Swift’s The Tortured Poets Department had released, during the same week I watched The Boy and the Heron. It too did not deliver what I expected or wanted. It was spare, and minimal, and sometimes clumsily written. But at other times, it catches me off-guard, moving from the aural equivalent of paint drying to a shadow lifting off a wall in your peripheral vision. I don’t know what I mean by that exactly. Messy writing is on-brand here, and I can’t help that. I find it beguiling.

II. Mahito escapes

The Boy and the Heron, rather than providing comfort in my painrot period, left me with a sense of dissatisfaction; of expectations placed upon me. The primary source of this effect was Hisaishi’s score. It is (uncharacteristically for his collaborations with Miyazaki) quite spare, leaning heavily on the piano and only sometimes embellishing with the remainder of the orchestra.

And I would say these embellishments happen less frequently than they usually should for a movie made by Miyazaki. The Boy and the Heron is a bizarre tale told in a lush miasma of interwoven realities. It’s the kind of story you would want to be accompanied by sumptuous, lyrical, romantic, fantastical music. But that’s just not what you get.

So while I wanted, and felt I needed, an escape into a Hisaishi fantasy soundscape, his compositions for The Boy and the Heron feel more instructive than fabulous. If his Spirited Away score felt like having a fairytale read to you in your childhood bedroom, The Boy and the Heron sounds like the next morning, when the sunrise hasn’t evaporated the last dew of the dreamworld yet, but your mother does need you to make breakfast for the family. And while you fry up some eggs and the bacon she’s defrosted, she pores over some grown-up paperwork that you assume is all “bills.” There is still a faint touch of magic in the world of your home, and in the pancakes you lovingly douse in syrup for your younger sister.

I. you only watch

There is also a haunting of a precarity you don’t understand but can feel. All of this could go away, and judging by your mother’s sounds of frustration and stressed shuffling of stationery, that may already be happening. But for now the syrup and butter on top of pancakeas is bright and tasty.

IV. the rest

There is nothing here like Hisaishi’s other music. The orchestral swells of One Summer Day, the bobbing whimsy of The Merry-Go-Round of Life, the electrified, chitinous textures of The Princess Who Loves Insects. Instead, for The Boy and the Heron, Hisaishi gives us spare soundscapes like White Wall, Memories, and Ask Me Why (Mother’s Message) which are more a map of an unknown world than a doorway into it. And it works. The Boy and the Heron was, at least to me, about the tension between personal pain and responsibility to others.

Mahito, the main protagonist, is a young boy who loses his mother in a hospital fire. It is a trauma beyond reckoning for such a young person. And the world around him does not rest long enough to allow him a neat and tidy grieving process. Instead, the world and its actors — human, animal, inanimate — all provoke him to remember. To leap into alternative realities where he might hope to save his mother before what happened to her happened. To build a life over again before the mess of it.

V. the suddenness

Before you realise it, it’s over. Credits roll. You have to make closing comments with people you will likely never see again, share perspectives on a movie that made no sense. Make a joke about being recently divorced that lands surprisingly well. Split an uber home. First yours, then hers.

Then it’s just you, the soundtrack murmuring in your head, and your dog who waited for you to come home.

Boygenius, ‘Afraid of Heights’ (Track 2 on the rest, Interscope Records, 2023)

I think I photobombed some actors’ red carpet group photo — best case scenario it was the back of my head. Nervous to meet a group of strangers I realised too late what was happening and turned away at the last moment. So there is a chance that, at 6’3”, I turned too late and my blurry face is hanging over some actor’s debut moment like 19th-Century spirit photography. It was a real good start to meeting new people this year.

Nick Hart, ‘The Radical Pacifism of Hayao Miyazaki’ (April 8, 2024, Counter Arts)

Shanee Edwards, ‘Hayao Miyazaki Says 'Ma' is an Essential Storytelling Tool’ (November 27, 2023, Screencraft.com)

Shy Thompson, ‘Review: The Boy and the Heron (Original Soundtrack)’ (January 27, 2024, Pitchfork.com)

as always, your work is evocative and absolutely captivating. as always, i am in awe. you're incredible, truly.